1. Core Claims by Each Participant

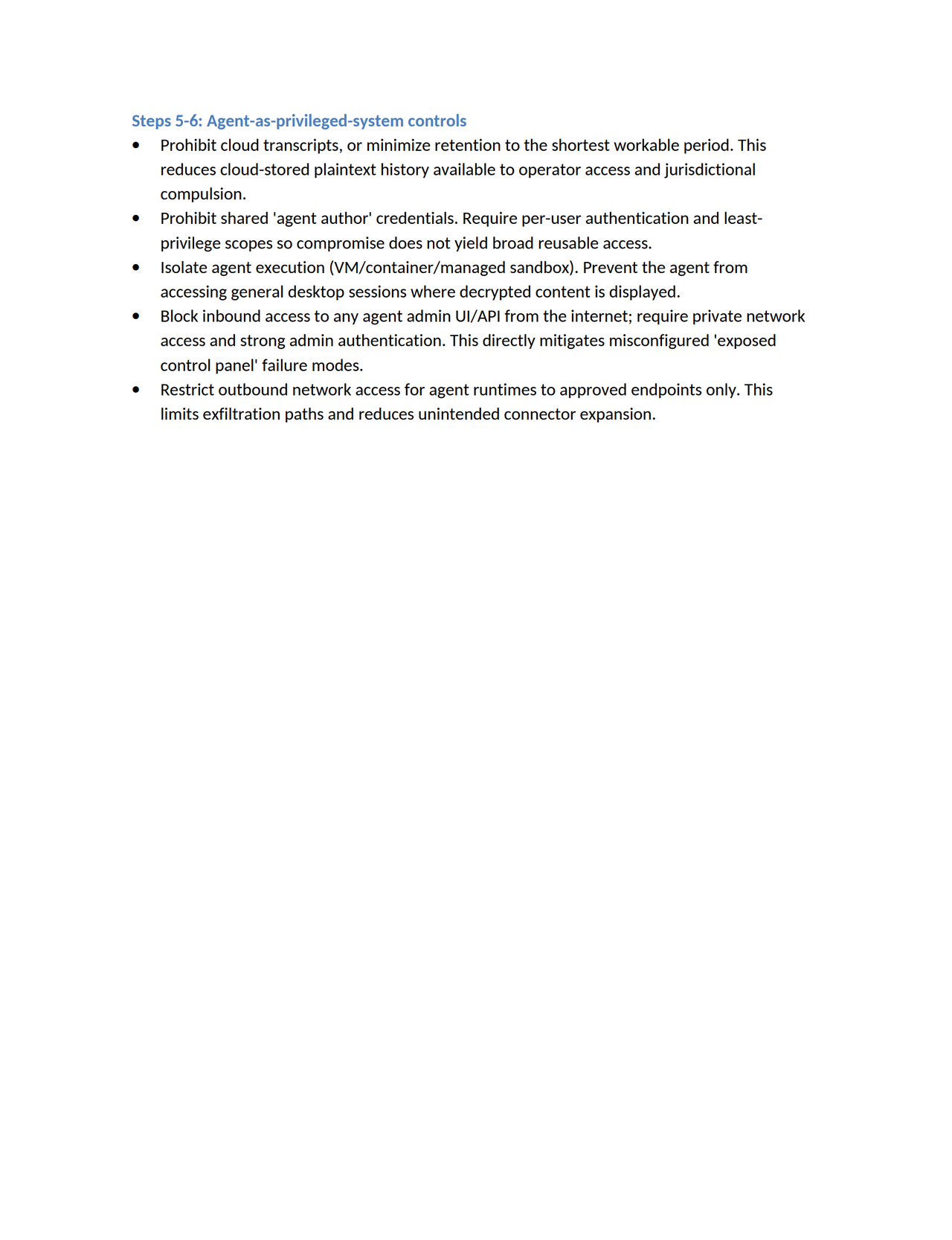

Tim Bouma (Privacy Advocate Perspective): Tim’s analysis of Article 9 centers on its broad logging mandate and the power dynamics it creates. Legally, he notes that Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2024/2979 requires wallet providers to record all user transactions with relying parties – even unsuccessful ones – and retain detailed logs (timestamp, relying party ID, data types disclosed, etc.)

. These logs must be kept available for as long as laws require, and providers can access them whenever necessary to provide services, albeit only with the user’s explicit consent (in theory). Tim argues that, while intended to aid dispute resolution and accountability, this effectively enlists wallet providers and relying parties as “surveillance partners” to everything a user does with their digital wallet. He warns that authorities wouldn’t even need to ask the user for evidence – they could simply compel the provider to hand over a “full, cryptographically verifiable log of everything you did,” which is extremely convenient for investigations. In his view, Article 9’s logging rule is well-intentioned but naïve about power: it assumes providers will resist government overreach, that user consent for access will remain meaningful, that data retention laws will stay proportionate, and that “exceptional access” will remain truly exceptional. Technically, Tim emphasizes the security and privacy risks of this approach. A centralized, provider-accessible log of all user activity creates a single, lucrative attack surface and “meticulously engineered register” of personal data. If such logs are breached or misused, it’s not merely a leak of isolated data – it’s a complete, verifiable record of a citizen’s interactions falling into the wrong hands. He notes this design violates fundamental distributed-systems principles by concentrating too much trust and risk in one place. Tim (and those sharing his view) argue that because the EU wallet’s security model relies heavily on the user’s sole control of credentials (“possession as the only security anchor”), the system overcompensates by imposing “pervasive control and logging” to achieve assurance. He suggests this is an unsustainable architecture, especially in multi-hop scenarios (e.g., where credentials flow through several parties). Instead, Tim alludes to cryptographic solutions like Proof of Continuity that could provide accountability without such invasive logging. In short, Tim’s claim is that Article 9 is not explicitly a surveillance measure, but a “pre-surveillance clause” – it lays down the infrastructure that could be rapidly repurposed for surveillance without changing a word of the regulation. The danger, he concludes, is not in what Article 9 does on day one, but that it does “exactly enough to make future overreach cheap, fast, and legally deniable”

Alex DiMarco (Accountability vs. Privacy Mediator): Alex’s comments and follow-up post focus on the tension between legal accountability and user privacy/control. Legally, he acknowledges why Article 9 exists: it “mandates transaction logging to make disputes provable”, i.e. to ensure there’s an audit trail if something goes wrong.

This ties into the EU’s high assurance requirements – a Level of Assurance “High” wallet must enable non-repudiation and forensic audit of transactions in regulated scenarios. Alex recognizes this need for accountability and legal compliance (for instance, proving a user truly consented to a transaction or detecting fraud), as well as obligations like enabling revocation or reports to authorities (indeed Article 9(4) requires logging when a user reports a relying party for abuse). However, he contrasts this with privacy and user agency expectations.

Technically, Alex stresses who holds and controls the logs. He argues that “the moment those logs live outside exclusive user control, ‘personal’ becomes a marketing label”.

In other words, a Personal Digital Wallet ceases to be truly personal if an external provider can peek into or hand over your activity records. He likens a centrally logged wallet to a bank card: highly secure and auditable, yes, but also “deeply traceable” by design. Using Tim’s “Things in Control” lens (a reference to deciding who ultimately controls identity data), Alex frames the issue as: “Who can open the safe, and who gets to watch the safe being opened?”. Here, the “safe” is the log of one’s transactions. If only the user can open it (i.e. if logs are user-held and encrypted), the wallet aligns with privacy ideals; if the provider or others can routinely watch it being opened (provider-held or plaintext logs), then user control is an illusion.

Alex’s core claim is that Article 9’s implementation must be carefully scoped: accountability can’t come at the cost of turning a privacy-centric wallet into just another traceable ID card. He likely points out that the regulation does attempt safeguards – e.g. logs should be confidential and only accessed with user consent – but those safeguards are fragile if, by design, the provider already aggregates all the data.

Technically, Alex hints at solutions like tamper-evident and user-encrypted logs: logs could be cryptographically sealed such that providers cannot read them unless the user allows. He also highlights privacy-preserving features built into the EUDI Wallet framework (and related standards) – for example, selective disclosure of attributes and pseudonymous identifiers for relying parties – which aim to minimize data shared per transaction

. His concern is that extensive logging might undermine these features by creating a backchannel where even the minimal disclosures get recorded in a linkable way. In sum, Alex navigates the middle ground: he validates the legal rationale (dispute resolution, liability, trust framework obligations) but insists on questioning the implementation: Who ultimately controls the data trail? If control tilts away from the user, the wallet risks becoming, in privacy terms, “high-assurance” for authorities but low-assurance for personal privacy.

Steffen Schwalm (Legal Infrastructure Expert Perspective): Steffen – representing experts in digital identity infrastructure and trust services – emphasizes the necessity and manageability of Article 9’s logging from a compliance standpoint. Legally, he likely argues that a European Digital Identity Wallet operating at the highest assurance level must have robust audit and traceability measures. For instance, if a user presents a credential to access a service, there needs to be evidence of who, when, and what data was exchanged, in case of disputes or fraud allegations. This requirement is consistent with long-standing eIDAS and trust-framework practices where audit logs are kept by providers of trust services (e.g. CAs, QSCDs) for a number of years. Steffen might point out that Article 9 was a deliberate policy choice: it was “forced into the legal act by [the European] Parliament” to ensure a legal audit trail, even if some technical folks worried about privacy implications.

The rationale is that without such logs, it would be difficult to hold anyone accountable in incidents – an unacceptable outcome for government-regulated digital identity at scale. He likely references GDPR’s concept of “accountability” and fraud prevention laws as justifications for retaining data. Steffen’s technical stance is that logging can be implemented in a privacy-protective and controlled manner. He would note that Article 9 explicitly requires integrity, authenticity, and confidentiality for logs – meaning logs should be tamper-proof (e.g. digitally signed and timestamped to detect any alteration) and access to their content must be restricted. In practice, providers might store logs on secure servers or hardware security modules with strong encryption, treating them like sensitive audit records. Steffen probably disputes the idea that Article 9 is “surveillance.” In the debate, he might underscore that logs are only accessible under specific conditions: the regulation says provider access requires user consent, and otherwise logs would only be handed over for legal compliance (e.g. a court order). In normal operation, no one is combing through users’ logs at will – they exist as a dormant safety net. He might also highlight that the logged data is limited (no actual credential values, only metadata like “user shared age verification with BankX on Jan 5”), which by itself is less sensitive than full transaction details. Moreover, “selective disclosure” protocols in the wallet mean the user can often prove something (like age or entitlement) without revealing identity; the logs would reflect that a proof was exchanged, but not necessarily the user’s name or the exact attribute value. In Steffen’s view, architecture can reconcile logs with privacy by using techniques such as pseudonymous identifiers, encryption, and access control. For example, the wallet can generate a different pseudonymous user ID for each relying party – so even if logs are leaked, they wouldn’t directly reveal a user’s identity across services. He might also mention that advanced standards (e.g. CEN ISSS or ETSI standards for trust services) treat audit logs as qualified data – to be protected and audited themselves. Finally, Steffen could argue that without central transaction logs, a Level-High wallet might not meet regulatory scrutiny. If a crime or security incident occurs, authorities will ask “what happened and who’s responsible?” – and a provider needs an answer. User-held evidence alone might be deemed insufficient (users could delete or fake data). Thus, from the infrastructure perspective, Article 9’s logging is a lawful and necessary control for accountability and security – provided that it’s implemented with state-of-the-art security and in compliance with data protection law (ensuring no use of logs for anything beyond their narrow purpose).

2. How Legal Requirements and Technical Design Intersect

The debate vividly illustrates the fusion – and tension – between legal mandates and technical architecture in the EU’s digital identity framework. On one hand, legal requirements are shaping the system’s design; on the other, technical architecture can either bolster or undermine the very privacy and accountability goals the law professes.

Legal Requirements Driving Architecture: Article 9 of Regulation 2024/2979 is a prime example of law dictating technical features. The law mandates that a wallet “shall log all transactions” with specific data points.

This isn’t just a policy suggestion – it’s a binding rule that any compliant wallet must build into its software. Why such a rule? Largely because the legal framework (the eIDAS 2.0 regulation) demands a high level of assurance and accountability. Regulators want any misuse, fraud, or dispute to be traceable and provable. For instance, if a user claims “I never agreed to share my data with that service!”, the provider should have a reliable record of the transaction to confirm what actually happened. This hews to legal principles of accountability and auditability – also reflected in GDPR’s requirement that organizations be able to demonstrate compliance with data processing rules. In fact, the European Data Protection Supervisor’s analysis of digital wallets notes that they aim to “strengthen accountability for each transaction” in both the physical and digital world.

So, the law prioritizes a capability (comprehensive logging) that ensures accountability and evidence.

This legal push, however, directly informs the system architecture: a compliant wallet likely needs a logging subsystem, secure storage (potentially server-side) for log data, and mechanisms for retrieval when needed by authorized parties. It essentially moves the EU Digital Identity Wallet away from a purely peer-to-peer, user-centric tool toward a more client-server hybrid – the wallet app might be user-controlled for daily use, but there is a back-end responsibility to preserve evidence of those uses. Moreover, legal provisions like “logs shall remain accessible as long as required by Union or national law” all but ensure that logs can’t just live ephemerally on a user’s device (which a user could wipe at any time). The architecture must guarantee retention per legal timeframes – likely meaning cloud storage or backups managed by the provider or a government-controlled service. In short, legal durability requirements translate to technical data retention implementations.

Architecture Upholding or Undermining Privacy: The interplay gets complicated because while law mandates certain data be collected, other laws (namely, the GDPR and the eIDAS regulation’s own privacy-by-design clauses) insist that privacy be preserved to the greatest extent possible. This is where architectural choices either uphold those privacy principles or weaken them. For example, nothing in Article 9 explicitly says the logs must be stored in plaintext on a central server visible to the provider. It simply says logs must exist and be accessible to the provider when necessary (with user consent).

A privacy-by-design architecture could interpret this in a user-centric way: the logs could be stored client-side (on the user’s device) in encrypted form, and only upon a legitimate request would the user (or an agent of the user) transmit the needed log entries to the provider or authority. This would satisfy the law (the records exist and can be made available) while keeping the provider blind to the data by default. Indeed, the regulation’s wording that the provider can access logs “on the basis of explicit prior consent by the user” suggests an architectural door for user-controlled release.

In practice, however, implementing it that way is complex – what if the user’s device is offline, lost, or the user refuses? Anticipating such issues, many providers might opt for a simpler design: automatically uploading logs to a secure server (in encrypted form) so that they are centrally stored. But if the encryption keys are also with the provider, that veers toward undermining privacy – the provider or anyone who compromises the provider could read the logs at will, consent or not. If, on the other hand, logs are end-to-end encrypted such that only the user’s key can decrypt them, the architecture leans toward privacy, though it complicates on-demand access. This shows how architecture can enforce the spirit of the law or just the letter of it. A design strictly following the letter (log everything, store it somewhere safe) might meet accountability goals but do so in a privacy-weakening way (central troves of personal interaction data). A more nuanced design can fulfill the requirement while minimizing unintended exposure.

Another blending of legal and technical concerns is seen in the scope of data collected. The regulation carefully limits logged information to “at least” certain metadata – notably, it logs what type of data was shared, but not the data itself. For instance, it might record that “Alice’s wallet presented an age verification attribute to Service X on Jan 5, 2026” but not that Alice’s birthdate is 1990-01-01. This reflects a privacy principle (don’t log more than necessary) baked into a legal text. Technically, this means a wallet might store just attribute types or categories in the log. If implemented correctly, that reduces risk: even if logs are accessed, they don’t contain the actual sensitive values – only that certain categories of information were used. However, even metadata can be revealing. Patterns of where and when a person uses their wallet (and what for) can create a rich profile. Here again, architecture can mitigate the risk: for example, employing pseudonyms. Article 14 of the same regulation requires wallets to support generating pseudonymous user identifiers for each relying party. If the logs leverage those pseudonyms, an entry might not immediately reveal the user’s identity – it might say user XYZ123 (a pseudonym known only to that relying party) did X at Service Y. Only if you had additional info (or cooperated with the relying party or had the wallet reveal the mapping) could you link XYZ123 to Alice. This architectural choice – using pairwise unique identifiers – is directly driven by legal privacy requirements (to minimize linkability).

But it requires careful implementation: the wallet and underlying infrastructure must manage potentially millions of pseudonymous IDs and ensure they truly can’t be correlated by outsiders. If designers shortcut this (say, by using one persistent identifier or by letting the provider see through the pseudonyms), they erode the privacy that the law was trying to preserve through that mechanism.

Furthermore, consider GDPR’s influence on architecture. GDPR mandates data protection by design and default (Art. 25) and data minimization (Art. 5(1)©). In the context of Article 9, this means the wallet system should collect only what is necessary for its purpose (accountability) and protect it rigorously. A privacy-conscious technical design might employ aggregation or distributed storage of logs to avoid creating a single comprehensive file per user. For example, logs could be split between the user’s device and the relying party’s records such that no single entity has the full picture unless they combine data during an investigation (which would require legal process). This distributes trust. In fact, one commenter in the debate half-joked that a “privacy wallet provider” could comply in a creative way: “shard that transaction log thoroughly enough and mix it with noise” so that it’s technically compliant but “impossible to use for surveillance”.

This hints at techniques like adding dummy entries or encrypting logs in chunks such that only by collating multiple pieces with user consent do they become meaningful. Such approaches show how architecture can uphold legal accountability on paper while also making unwarranted mass-surveillance technically difficult – thereby upholding the spirit of privacy law.

At the same time, certain architectural decisions can weaken legal accountability if taken to the extreme, and the law pushes back against that. For instance, a pure peer-to-peer architecture where only the user holds transaction evidence could undermine the ability to investigate wrongdoing – a malicious user could simply delete incriminating logs. That’s likely why the regulation ensures the provider can access logs when needed.

The architecture, therefore, has to strike a balance: empower the user, but not solely the user, to control records. We see a blend of control: the user is “in control” of day-to-day data sharing, but the provider is in control of guaranteeing an audit trail (with user oversight). It’s a dual-key approach in governance, if not in actual cryptography.

Finally, the surrounding legal environment can re-shape architecture over time. Tim Bouma’s cautionary point was that while Article 9 itself doesn’t mandate surveillance, it enables it by creating hooks that other laws or policies could later exploit.

For example, today logs may be encrypted and rarely accessed. But tomorrow, a new law could say “to fight terrorism, wallet providers must scan these logs for suspicious patterns” – suddenly the architecture might be adjusted (or earlier encryption requirements relaxed) to allow continuous access. Or contracts between a government and the wallet provider might require that a decrypted copy of logs be maintained for national security reasons. These scenarios underscore that legal decisions (like a Parliament’s amendment or a court ruling) can reach into the technical architecture and tweak its knobs. A system truly robust on privacy would anticipate this by hard-coding certain protections – for instance, if logs are end-to-end encrypted such that no one (not even the provider) can access them without breaking cryptography, then even if a law wanted silent mass-surveillance, the architecture wouldn’t support it unless fundamentally changed. In other words, architecture can be a bulwark for rights – or, if left flexible, an enabler of future policy shifts. This interplay is why both privacy advocates and security experts are deeply interested in how Article 9 is implemented: the law sets the minimum (logs must exist), but the implementation can range from privacy-preserving to surveillance-ready, depending on technical and governance choices.

3. Conclusion: Is “Pre‑Surveillance” a Valid Concern, and Are There Privacy-Preserving Alternatives?

Does Article 9 enable a “pre-surveillance” infrastructure? Based on the debate and analysis above, the criticism is valid to a considerable extent. Article 9 builds an extensive logging capability into the EU Wallet system – essentially an always-on, comprehensive journal of user activities, meticulously detailed and cryptographically verifiable.

By itself, this logging infrastructure is neutral – it’s a tool for accountability. However, history in technology and policy shows that data collected for one reason often gets repurposed. Tim Bouma and privacy advocates cite the uncomfortable truth: if you lay the rails and build the train, someone will eventually decide to run it. In this case, the “rails” are the mandated logs and the legal pathways to access them. Today, those pathways are constrained (user consent or lawful request). But tomorrow, a shift in political winds or a reaction to a crisis could broaden access to those logs without needing to amend Article 9 itself. For example, a Member State might pass an emergency law saying “wallet providers must automatically share transaction logs with an intelligence agency for users flagged by X criteria” – that would still be “as required by national law” under Article 9(6). Suddenly, what was dormant data becomes active surveillance feed, all through a change outside the wallet regulation. In that sense, Article 9’s infrastructure is pre-positioned for surveillance – or “pre-surveillance,” as Tim dubbed it. It’s akin to installing CCTV cameras everywhere but promising they’ll remain off; the capability exists, awaiting policy to flip the switch. As one commenter noted, the danger is that Article 9 “does exactly enough to make future overreach cheap, fast, and legally deniable”.

Indeed, having a complete audit trail on every citizen’s wallet use ready to go vastly lowers the barrier for state surveillance compared to a system where such data didn’t exist or was decentralized.

It’s important to acknowledge that Article 9 was not written as a mass surveillance measure – its text and the surrounding eIDAS framework show an intent to balance accountability with privacy (there are consent requirements, data minimization, etc.).

But critics argue that even a well-intended logging mandate can erode privacy incrementally. For example, even under current rules, consider the concept of “voluntary” consent for provider access. In practice, a wallet provider might make consent to logging a condition for service – effectively forcing users to agree. Then “consent” could be used to justify routine analytics on logs (“to improve the service”) blurring into surveillance territory. Additionally, logs might become a honeypot for law enforcement fishing expeditions or for hackers if the provider’s defenses fail. The mere existence of a rich data trove invites uses beyond the original purpose – a phenomenon the privacy community has seen repeatedly with telecom metadata, credit card records, etc. David Chaum’s 1985 warning rings true: the creation of comprehensive transaction logs can enable a “dossier society” where every interaction can be mined and inferred.

Article 9’s logs, if not tightly guarded and purpose-limited, could feed exactly that kind of society (e.g. linking a person’s medical, financial, and social transactions to profile their life). So, labeling the infrastructure as “pre-surveillance” is not hyperbole – it’s a recognition that surveillance isn’t just an act, but also the capacities that make the act feasible. Article 9 unquestionably creates a capacity that authoritarian-leaning actors would find very useful. In sum, the critique is valid: Article 9 lays down an architecture that could facilitate surveillance with relative ease. The degree of risk depends on how strictly safeguards (legal and technical) are implemented and upheld over time, but from a structural standpoint, the foundation is there.

Can user-controlled cryptographic techniques satisfy accountability without provider-readable logs?

Yes – at least in theory and increasingly in practice – there are strong technical approaches that could reconcile the need for an audit trail with robust user privacy and control. The heart of the solution is to shift from provider-trusted logging to cryptographic, user-trusted evidence. For example, instead of the provider silently recording “Alice showed credential X to Bob’s Service at 10:00,” the wallet itself could generate a cryptographically signed receipt of the transaction and give it to Alice (and perhaps Bob) as proof. This receipt might be a zero-knowledge proof or a selectively disclosed token that confirms the event without revealing extraneous data. If a dispute arises, Alice (or Bob) can present this cryptographic proof to an arbitrator or authority, who can verify its authenticity (since it’s signed by the wallet or issuing authority) without the provider ever maintaining a dossier of all receipts centrally. In this model, the user (and relevant relying party) hold the logs by default – like each keeps a secure “transaction receipt” – and the provider is out of the loop unless brought in for a specific case. This user-centric logging can satisfy legal accountability because the evidence exists and is verifiable (tamper-evident), but it doesn’t reside in a big brother database.

One concrete set of techniques involves end-to-end encryption (E2EE) and client-side logging. For instance, the wallet app could log events locally in an encrypted form where only the user’s key can decrypt. The provider might store a backup of these encrypted logs (to meet retention rules and in case the user loses their device), but without the user’s consent or key, the entries are gibberish. This way, the provider fulfills the mandate to “ensure logs exist and are retained,” but cannot read them on a whim – they would need the user’s active cooperation or a lawful process that compels the user or a key escrow to unlock them.

Another approach is to use threshold cryptography or trusted execution environments: split the ability to decrypt logs between multiple parties (say, the user and a judicial authority) so no single party (like the provider) can unilaterally surveil. Only when legal conditions are met would those pieces combine to reveal the plaintext logs. Such architectures are complex but not unprecedented in high-security systems.

Zero-knowledge proofs (ZKPs) are especially promising in this domain. ZKPs allow a user to prove a statement about data without revealing the data itself. For digital identity, a user could prove “I am over 18” or “I possess a valid credential from Issuer Y” without disclosing their name or the credential’s details. The EU wallet ecosystem already anticipates selective disclosure and ZKP-based presentations (the ARF even states that using a ZKP scheme must not prevent achieving LoA High).

When a user authenticates to a service using a ZKP or selective disclosure, what if the “log” recorded is also a kind of zero-knowledge attestations? For example, a log entry could be a hash or commitment to the transaction details, time-stamped and signed, possibly even written to a public ledger or transparency log. This log entry by itself doesn’t reveal Alice’s identity or what exactly was exchanged – it might just be a random-looking string on a public blockchain or an audit server. However, if later needed, Alice (or an investigator with the right keys) can use that entry to prove “this hash corresponds to my transaction with Service X, and here is the proof to decode it.” In effect, you get tamper-evident, append-only public logs (fulfilling integrity and non-repudiation) but privacy is preserved because only cryptographic commitments are public, not the underlying personal data. In the event of an incident, those commitments can be revealed selectively to provide accountability. This is analogous to Certificate Transparency in web security – every certificate issuance is logged publicly for audit, but the actual private info isn’t exposed unless you have the certificate to match the log entry.

Another concept raised in the debate was “Proof of Continuity.” While the term sounds abstract, it relates to ensuring that throughout a multi-hop identity verification process, there’s a continuous cryptographic link that can be audited.

Instead of relying on a central log to correlate steps, each step in a user’s authentication or credential presentation could carry forward a cryptographic proof (a token, signature, or hash) from the previous step. This creates an unbroken chain of evidence that the user’s session was valid without needing a third party to log each step. If something goes wrong, investigators can look at the chain of proofs (provided by the user or by intercepting a public ledger of proofs) to see where it failed, without having had a central server logging it in real-time. In essence, authority becomes “anonymous or accountable by design, governed by the protocol rather than external policy,” and the “wallet becomes a commodity”.

That is, trust is enforced by cryptographic protocol (you either have the proofs or you don’t) not by trusting a provider to have recorded and later divulged the truth. This design greatly reduces the privacy impact because there isn’t a standing database of who did what – there are just self-contained proofs held by users and maybe published in obfuscated form.

Of course, there are challenges with purely user-controlled accountability. What if the user is malicious or collusive with a fraudulent party? They might refuse to share logs or even tamper with their device-stored records (though digital signatures can prevent tampering). Here is where a combination of approaches can help: perhaps the relying parties also log receipts of what they received, or an independent audit service logs transaction hashes (as described) for later dispute. These ensure that even if one party withholds data, another party’s evidence can surface. Notably, many of these techniques are being actively explored in the identity community. For example, some projects use pairwise cryptographic tokens between user and service that can later be presented as evidence of interaction, without a third party seeing those tokens in the moment. There are also proposals for privacy-preserving revocation systems (using cryptographic accumulators or ZK proofs) that let someone verify a credential wasn’t revoked at time of use without revealing the user’s identity or requiring a central query each time.

All these are ways to satisfy the intent of logging (no one wants an undetectable fraudulent transaction) without the side effect of surveilling innocents by default.

In the end, it’s a matter of trust and control: Article 9 as written leans on provider trust (“we’ll log it, but trust us and the law to only use it properly”). Privacy-preserving architectures lean on technical trust (“we’ve designed it so it’s impossible to abuse the data without breaking the crypto or obtaining user consent”).

Many experts argue that, especially in societies that value civil liberties, we should prefer technical guarantees over policy promises. After all, a robust cryptographic system can enforce privacy and accountability simultaneously – for example, using a zero-knowledge proof, Alice can prove she’s entitled to something (accountability) and nothing more is revealed (privacy).

This approach satisfies regulators that transactions are legitimate and traceable when needed, but does not produce an easily exploitable surveillance dataset.

To directly answer the question: Yes, user-controlled cryptographic techniques can, in principle, meet legal accountability requirements without requiring logs readable by the provider. This could involve the wallet furnishing verifiable but privacy-protecting proofs of transactions, implementing end-to-end encrypted log storage that only surfaces under proper authorization, and leveraging features like pseudonymous identifiers and selective disclosure that are already part of the EUDI Wallet standards.

Such measures ensure that accountability is achieved “on demand” rather than through continuous oversight. The legal system would still get its evidence when legitimately necessary, but the everyday risk of surveillance or breach is dramatically reduced. The trade-off is complexity and perhaps convenience – these solutions are not as straightforward as a plain server log – but they uphold the fundamental promise of a digital identity wallet: to put the user in control. As the EDPS TechDispatch noted, a well-designed wallet should “reduce unnecessary tracking and profiling by identity providers” while still enabling reliable transactions.

User-controlled logs and cryptographic proofs are exactly the means to achieve that balance of privacy and accountability by design.

Sources:

· Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2024/2979, Article 9 (Transaction logging requirements)[23][4]

· Tim Bouma’s analysis of Article 9 and its implications (LinkedIn posts/comments, Dec 2025)[7][6][9]

· Alex DiMarco’s commentary on the accountability vs privacy fault line in Article 9 (LinkedIn post, Jan 2026)[14][39]

· Expert debate contributions (e.g. Ronny K. on legislative intent[20] and Andrew H. on creative compliance ideas[29]) illustrating industry perspectives.

· European Data Protection Supervisor – TechDispatch on Digital Identity Wallets (#3/2025), highlighting privacy-by-design measures (pseudonyms, minimization) and the need to ensure accountability for transactions[36][24].

· Alvarez et al., Privacy Evaluation of the EUDIW ARF (Computers & Security vol.160, 2026) – identifies linkability risks in the wallet’s design and suggests PETs like zero-knowledge proofs to mitigate such risks[24][38].

[1] [5] [6] [7] [8] [9] [10] [11] [12] [13] [20] [24] [28] [29] [31] [36] [37] [38] EU Digital Identity Wallet Regulations: 2024/2979 Mandates Surveillance | Tim Bouma posted on the topic | LinkedIn

https://www.linkedin.com/posts/trbouma_european-digital-identity-wallet-european-activity-7412499259012325376-E5Bp

[2] [3] [4] [15] [18] [19] [21] [22] [23] [25] [26] [30] [32] [33] Understand the EU Implementing Acts for Digital ID | iGrant.io DevDocs

https://docs.igrant.io/regulations/implementing-acts-integrity-and-core-functions/

[14] [16] [17] [39] Who is in control – the debate over article 9 for the EU digital wallet | Alex DiMarco

https://www.linkedin.com/posts/dimarcotech-alex-dimarco_who-is-in-control-the-debate-over-article-activity-7414692978964750336-ohfV

[27] [34] #digitalwallets #eudiw | Tim Bouma | 24 comments

https://www.linkedin.com/posts/trbouma_digitalwallets-eudiw-activity-7412618695367311360-HiSp

[35] ANNEX 2 – High-Level Requirements – European Digital Identity Wallet

https://eudi.dev/1.9.0/annexes/annex-2/annex-2-high-level-requirements/

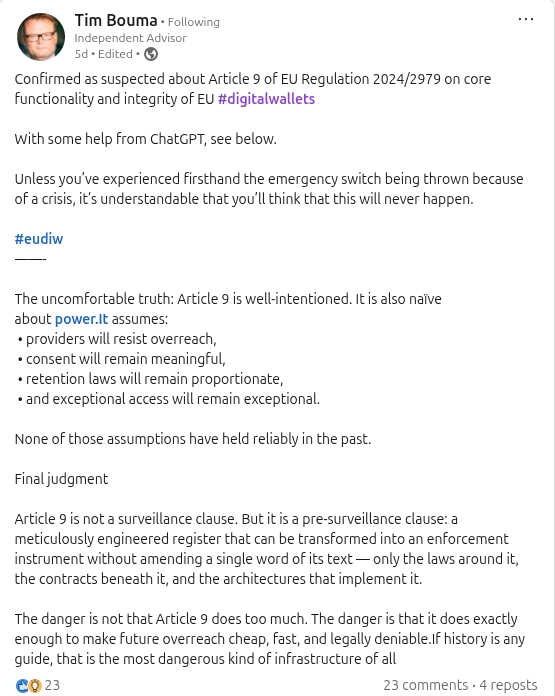

Microsoft seems to be repeating errors from its past in the pursuit of marketable “tools” and “features,” sacrificing safety and privacy for dominance. This is not a new pattern. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, Microsoft made a deliberate decision to integrate Internet Explorer directly into the operating system, not because it was the safest architecture, but because it was a strategic one. The browser became inseparable from Windows, not merely as a convenience, but as a lever to eliminate competition and entrench market control. The result was not only the well documented U.S. antitrust case, but a security disaster of historic scale, where untrusted web content was processed through deeply privileged OS components, massively expanding attack surface across the entire installed base. The record of that era is clear: integration was a business tactic first, and the security consequences were treated as collateral. https://www.justice.gov/

Microsoft seems to be repeating errors from its past in the pursuit of marketable “tools” and “features,” sacrificing safety and privacy for dominance. This is not a new pattern. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, Microsoft made a deliberate decision to integrate Internet Explorer directly into the operating system, not because it was the safest architecture, but because it was a strategic one. The browser became inseparable from Windows, not merely as a convenience, but as a lever to eliminate competition and entrench market control. The result was not only the well documented U.S. antitrust case, but a security disaster of historic scale, where untrusted web content was processed through deeply privileged OS components, massively expanding attack surface across the entire installed base. The record of that era is clear: integration was a business tactic first, and the security consequences were treated as collateral. https://www.justice.gov/